This is the first of a three-part blog post series based on a lecture presented by NGJ Executive Director, Dr Veerle Poupeye, at the Jamaica Music Museum’s Grounation programme of February 16, 2014. The lecture’s topic is relevant to the current Explorations II: Religion and Spirituality Exhibition, which continues until April 27, 2014.

The theme of this year’s Grounation series is “seeing sounds and hearing images” and my presentation invites you to do just that. I will not use sound in my presentation, but I will appeal to your imagination, to “see the sounds” and “hear the images” in the work of three major Jamaican artists: the painter and sculptor Mallica “Kapo” Reynolds, who was a Revival leader; the painter, sculptor and musical instrument-maker Everald Brown, who was a religious Rastafari leader and a pioneer of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church; and the sculptor William “Woody” Joseph, who had no specific religious affiliation but was part of the cultural sphere of Revival. Everald Brown is an artist I have focused on in my original research, writing, and curatorial work since the mid-1980s and I curated his retrospective for the National Gallery in 2004, so he will be my main case study in this presentation.

At first sight – and the pun is intentional – visual art may seem to speak an exclusively visual language. Yet we all know that to be untrue. Art arguably appeals to all the senses, most obviously also to touch but potentially also to taste, smell and, for that matter, hearing. Those who work in art museums and galleries know how difficult it is prevent visitors from touching the art on view, because it powerfully appeals to the sense of touch, and anybody who has spent some time in an artist’s studio must be familiar with the distinctive smells of various art materials. Most works of art are as such mute but there is a powerful connection between sound and vision which has played a major role in the development of art and music alike and from time immemorial. A 2008 Science Daily article asserted that music played an important role in the ritual production and use of ancient cave art and that early musical instruments, such as bone flutes, are therefore often found in close proximity to ancient cave paintings. The relationship between art and music and the capacity of one to support the other has also been a major preoccupation in modern art, for instance in the work of the Swiss artist Paul Klee, whose abstract paintings were often based on musical interpretation. Music and the visual are also closely intertwined in the popular music industry, in the production of record covers, posters, concert backdrops, fashions and other visual materials, and the association between reggae and graphic design has played an important role in the development of Jamaican visual culture, with several major local designers such as Neville Garrick emerging. More recently, with the development of video and digital art, actual sound has become part of many works of art and sound and music have thereby entered the conventionally hushed environment of the art museum and gallery. It is now a trend for galleries and museums to have a resident deejay to create soundscapes for the museum environment, as was recently done at the Tate Modern and, even, the venerable Metropolitan Museum.

But sound, and the other senses, can also be implied in a work of art, based on the evocative potential of the visual. You are now looking at Bush Have Ears, a painting from 1976 by Everald Brown, which was painted after he moved back from Kingston to the deep rural area of Murray Mountain, St Ann, not far from the Cockpit Country. And here you can see the real “bush”, as seen by me from his hilltop home in 2004, and immediately realize the connection between the Bush Have Ears Painting and Brown’s lived environment.

Brother Brown’s landscapes, and he painted many, depict a spiritually animated natural world, a landscape that is alive, listening and, no doubt, speaking in various tongues, to be revealed by the artist-mystic. And indeed, no matter how peaceful looking, no landscape is ever truly silent and I invite you to imagine the implied sounds that permeate this painting: the sound of the wind, rustling leaves, and perhaps some distant thunder; animal noises – insects, goats, a dog, a donkey, birds, lizards scurrying around, a rooster crowing; human voices – neighbours hailing each other, an animated discussion at the community bar and that characteristic clacking of domino stones; and, since this is Jamaica, perhaps even a sound system or at least a portable radio somewhere in the valley. Add to this the spiritual, ancestral murmurs Brown reveals in this landscape and I am sure you will agree with me that this painting is not mute at all. Examined this way, by “listening to the image” and by “seeing the sounds”, Bush Have Ears reveals a rich implied soundscape which is an integral part of the significance of this work.

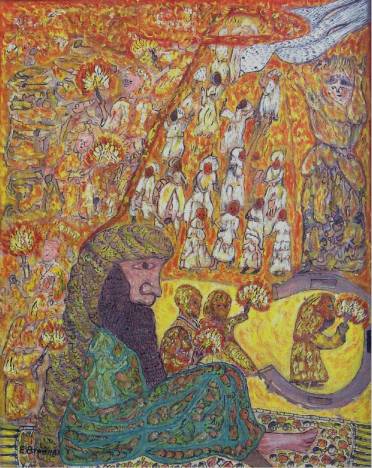

I could have done a similar exercise with many other works by Brother Brown, for instance his Country Life (1976), which more literally evokes the sounds of country life, or Everlasting King (1987), a visionary work that is full of apocalyptic spiritual “noise”. Likewise, a lot of Kapo’s work can be looked at in this way: for instance his Peaceful Quietness (1969), a landscape dominated by a large cotton tree, which is in the African-derived traditions regarded as the home of powerful spiritual presences, or his Royal Rooster (1967), because the rooster, of course, has to crow and thereby establishes a powerful aural presence in the environment which significantly amplifies its actual size.

2 replies on “SOUND AND VISION: MUSIC AND SOUND IN THE WORK OF KAPO, EVERALD BROWN AND WOODY JOSEPH – Part I”

This is really good. I like the emplacement of the artworks against the background of seeing the sounds and hearing the images…

Beautiful.